In the closing credits of his 2007 movie RATATOUILLE, director Brad Bird included a little easter egg for animators - a “Quality Assurance Guarantee” badge in the credits which informs the viewer that “no motion capture or other performance shortcuts were used in the production of the film.”

When asked about it, this is how Bird responded:

The “Guarantee” was my idea, not Pixar’s. It had zero to do with CARS or HAPPY FEET. It was a response to a trend at the time of making “animated” films with real-time motion capture rather than the frame-by-frame technique that I love and was proud of, that we had used on RATATOUILLE.

Bird clearly felt the cheap knock-off motion-captured films that studios like Blue Sky and Illumination were rushing out at the time lacked a certain human quality that you get automatically from the quirks and imperfections of traditional animation. Animators use all kinds of tricks to enhance the action on screen, such as smear frames, skipped frames, intentionally having characters go off-model for an exaggerated expression, etc. In addition, human artists inevitably have a personal “style” which can’t help but leak into their output.

But all of that is paved over with the machine-made smoothness of perfect tweens and morphing that you get from motion capture animation in which the computer simply tracks a figure and maps a 3D model onto it.

When you use automated software to generate as much of the movie as possible, and then generate as many movies as possible using that technique, the result is a lot of undifferentiated movies that all kind of feel samey and boring. This is captured pretty well by the “Dreamworks Face” phenomenon, where you can really tell that all these images were spit out by the same modelling and shading engine and not a lot of care or thought went into creating a unique look for each of the films.

The Slurry

I think this is the kind of thing Bird was trying to subtly fight back against by including a “Quality Assurance Guarantee” in the credits of his movie. Everything just kind of turning into an undifferentiated “pink slime” that doesn’t seem to have involved a human with a personal style or point of view in any part of the creative process.

The onset of generative AI technologies has created a similar problem with text and visual content writ large. Anybody can go to Bing Image Creator and gin up a graphic to slap on a blog post. Google search results have already been overrun by reams of auto-generated AI posts on any conceivable topic which game their SEO algorithms to ensure they appear at the top.

But, these things have a similar problem. The AI-generated images all have a similar “everything is made of smooth vinyl and lit with diffuse light from every side” look to them. The AI-generated blog posts all contain paragraphs of gobbledegook that talk around the subject at hand while incessantly repeating the SEO-targeted keywords without actually providing any useful information (or worse, provide factually incorrect information).

All this results in a feeling that everything you look at on the internet is now a part of this kind of undifferentiated slurry of “content” which got spit out by a machine but which lacks a certain human quality. I like Aardman studios films, not because they look super realistic with flawlessly smooth animation, but precisely because you can see the thumbprints on the claymation models.

Humans at Work

I think we need a Quality Assurance Guarantee for the internet, sort of like Brad Bird’s “no motion capture” guarantee for Ratatouille, to designate that no generative AI was used in the production of a given work. Like those old “this page best viewed in Netscape Navigator” badges you used to see on “Web 1.0” era pages.

To that end, I commissioned a human artist (wild, I know) to create the following graphic. It’s released under the creative commons ‘public domain’ license, so feel free to use it if you like.

Old Man Yells At Cloud

This may all make it seem like I’m some crank Luddite who hates all advances in modern technology. Not the case! I think there are some good uses for these kind of generative AI systems - notably Github Copilot, which is great at suggesting implementations in software code while programming. Copilot is trained specifically off of code released on Github under open-source licenses. This means that the authors of the code have specifically opted in to releasing their code for use for this kind of purpose.

Compare this to the more general LLM and AI image generators, which are trained off of unlicensed, copyrighted works for which the original artists have not been compensated by the AI companies, without the artists’ permission or knowledge. You can trivially “trick” these things with “prompt injection” into spitting out the complete contents of novels under copyright, verbatim. I’m not against all uses of AI, but I am against uses that un-ethically steal the result of human artists’ labor and flood the zone with inferior replicas of their works without compensation.

The thing AI is really good for is making suggestions, like Github Copilot. Some people have termed this “fancy autocomplete,” which is kind of what it’s doing. The language model uses statistical analysis of a large corpus of data to determine the statistically likely next thing you’re about to write based on what you have written so far. You could similarly use some of the more general purpose LLMs to suggest an outline for how to structure a blog post or paper you’re working on. I could see some AI-assisted drawing tools that suggest the next thing you’re about to draw based on the existing in-progress drawing being worked on. I don’t think there’s any issue with this kind of usage, where the AI is making a suggestion that the human user is then free to accept or reject (provided the model wasn’t trained off of stolen works).

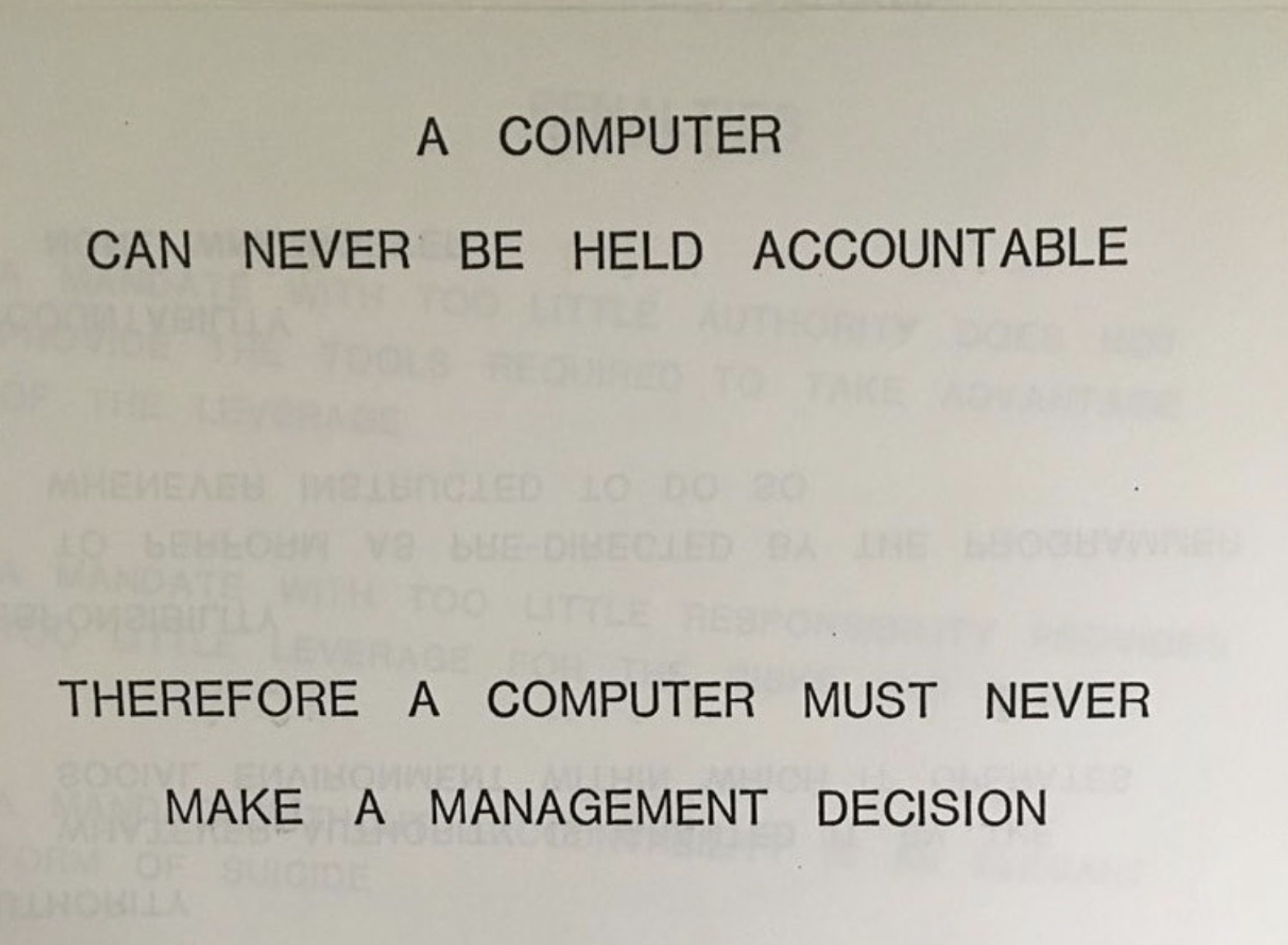

But, it’s very important not to skip that human part: you have to have a person involved to choose whether to accept or reject the suggestions made by the suggestion alorgithm. The problem is that a huge number of businesses seem intent on doing exactly that, bypassing the human check-valve and blindly accepting the AI’s predicted output as “correct” and taking actions based off of it, whether that means kicking off some business process, or giving people medical advice or psychoanalysis. These all seem very bad.

Respecting the Audience

In addition to all the moral and ethical problems with stealing copyrighted works and allowing the computer to make management decisions, there remains the issue of expecting people to pay for, or invest time in consuming, content that was auto-generated with an AI tool. I like the following quote:

Why should I be expected to read something you couldn’t be bothered to write?

Sadly, I’m not having any luck coming up with the original author of that quote (I guarantee it wasn’t an LLM). It gets to the central problem that I think Brad Bird was reacting against with his Quality Assurance Guarantee - if you’re going to use every “performance shortcut” available to you, up to and including auto-generating your entire output, you can’t really be surprised if your audience doesn’t feel particularly compelled to spend their time or money on consuming it.

All Things Must Pass

One detail of Bird’s statement above stands out to me: he says his Quality Assurance Guarantee badge was “a response to a trend at the time.”

It’s important to keep some perspective on these things. It may seem like we’ve been doomed to a permanent state of being buried alive under oceans of auto-generated AI sludge, but I think people are already starting to realize the limitations of trying to auto-generate news stories and entire novels and such with these tools.

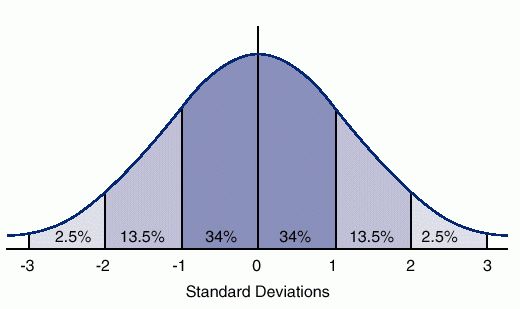

It’s a trend that will likely recede somewhat and find its level eventually. It’s always tempting when some trend is experiencing exponential growth to assume it’ll continue that way indefinitely, but most things actually end up being bell curves.

Regulation will (hopefully) reign in the copyright issues and unethical uses. Overexposure will swing the pendulum back in the other direction eventually. There will certainly be a long tail of legitimate uses for these things that evens out over time, but anybody who tells you the trend line is only going to keep going up and up exponentially forever is selling something.